I recently saw Red Letter Media’s take on Twin Peaks 3. Although I enjoyed their review, I was a little taken aback by one of the geeks saying he’d started watching Twin Perfect’s 4 hour analysis then dismissed it as ridiculous and simplistic; or rather, I was taken aback when he said that and then went on to echo many of Twin Perfect’s themes. I would agree that Twin Perfect oversimplifies; he here evinces what one could call an allegorical kind of mind.

Many years ago, when I first encountered Medieval allegory, I came to share Tolkien’s “cordial dislike” for the form. If a character is called Good Deeds, then surely that means he walks differently from a character called Courage, that he stands, blinks, breathes in a “Good Deeds” kind of way. Allegory must be absolute or it is not allegory.

But it is impossible to fully render allegory in fiction, as Dante found with his very humanly complex Commedia; so one could read the first cantos of Inferno as Dante learning how to write the Commedia, just as The Lord of the Rings begins like The Hobbit Part 2 and then becomes something very different, as Tolkien learnt how to write the book he was writing, in the process of writing it.

David Lynch’s films attract allegorical interpretation. So much as I dislike allegory, I had mixed feelings about Twin Perfect’s 4-hour long allegorical analysis – briefly put, he says Lynch identifies modern television as a metaphysical evil, so the battle between good & evil is a battle between the older, more worthwhile & human kinds of television, and the debased modern garbage. Twin Perfect is a good critic, marshalling evidence and explicating his theory in immense detail.

While I felt he sometimes stretches, I think he came close to Lynch’s authorial intent. The Red Letter Media guys felt that this kind of allegorical reading spoils the pleasure of the show, das Ding an sich, but I felt, peculiarly, that this was not so. Lynch is one of these rare makers, who can craft an allegorical work but so obscurely that it defies easy unriddling, without the obscurity ever seeming pointless or incidental. There are not many such creators; I could name the anonymous poet of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Kafka, Borges, Dante – where the evident weirdness invites allegorical interpretation, while remaining, as it were, das Ding an sich. I could say, echoing Wallace Stevens, that the creation “must resist the intelligence, almost successfully”.

I feel very friendly about David Lynch. Unlike Steven Spielberg, Tarantino, and other dubious types, I find Lynch to have a very human and gentle face. Perhaps I am wrong and he is a child rapist; but I doubt it.

For one thing, he clearly likes MILF and women of class.

“We are like the dreamer who dreams, and then lives inside the dream.”

The essence of Twin Peaks, as with True Detective Season 1, is the battle between good and evil as played out both in the world and in each individual soul.

Lynch I think began with the paradigm of good vs bad television; the former inspiring thought & self-examination; the latter offering mindless entertainment; but as a true creator Lynch fashioned resonance chambers of his personal concerns & fears & loves, so even without caring about such affairs the attentive viewer could nonetheless sense the pulsing evil at the heart of this conflict,

and the goodness it opposes. Thus, a heavily allegorical, almost encrypted work will fascinate those with the intellectual & emotional capacity; those who sense the primacy of good and evil.

Some wonder that David Lynch could work in what Vox Day calls the Hellmouth, Hollywood. Well, I would agree with Twin Perfect: one could plausibly see Mulholland Drive as Lynch’s disgust at Hollywood – not merely the financial corruption, but also the real evil at the heart of it, the sexual abuse and human trafficking.

Those more on the Right like to criticise anyone who doesn’t call out the, uh, well, the particular demographic category that often overlaps with such evils as we perceive it. I suspect Lynch is fully aware. In Twin Peaks, it seems that the root of the evil is an entity called “Judy” and while we are told this comes from Chinese, well, uh, umm, yeah. Let’s just say that anyone who speaks German, contemplating [redacted] and [redacted], and [redacted], and noticing certain commonalities, might wonder if Judy as the supreme evil might mean something else; hence Agent Phillip Jeffries, David Bowie’s nervy “I’m not going to talk about Judy, in fact we’re not going to talk about Judy at all”. What exactly is it, in Hollywood, that cannot be discussed?

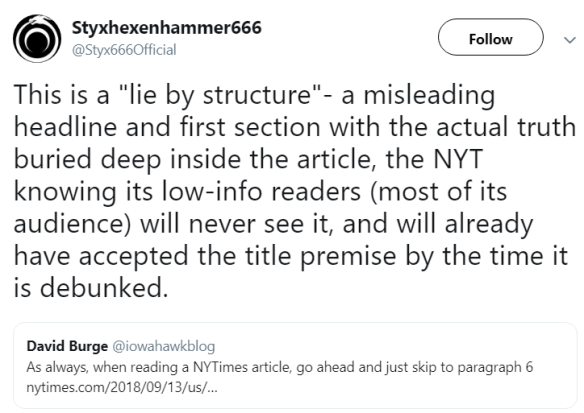

And if one must keep silent, then all the more reason to develop an allegorical imagination.